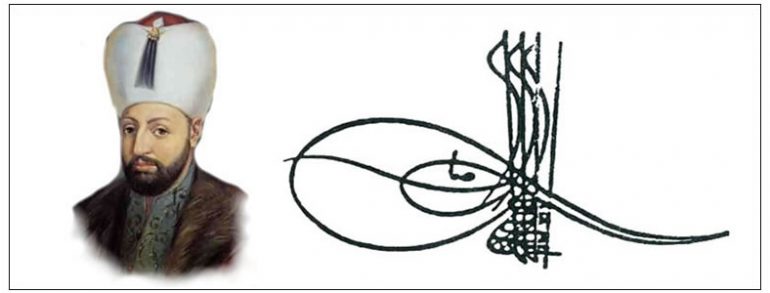

(1590, 1603-1617)

What would you do, if you had only 27 years to live? If you never thought about it, the story of Sultan Ahmed, the creator of the signature religious complex of the Blue Mosque of Istanbul, may give you an idea.

Ahmed’s Father, Sultan Mehmed III (1566, 1595-1603)

Ahmed was born into a royal family on 18 April 1590 in Manisa, Turkey, where his father, Sultan Mehmed III, was the princely governor. Within the harem, he had a good childhood with his older and younger brothers, Mahmud, and Mustafa respectively, and with his mother, Handan Sultan. She was very protective of her child and spent plenty of time with Ahmed. His family moved to the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul in 1595, as Mehmed III (1595-1603) became the new sultan upon the death of his grandfather, Sultan Murad III (1574-1595). Moving to a new palace in Istanbul must have been fun for the boys, as their life was limited within the walls of the Harem; the bigger the palace, the bigger the harem.

Mehmed III had a different agenda in his mind, or it was the agenda of Mehmed’s mother, Safiye Valide Sultan, though nobody will ever know for sure. The agenda was revealed in the first days of the throne. It was an attempt to secure his sultanic position by applying the law of sultanic fratricide (x), which means clearing all the obstacles and alternatives in his ruling. Thereby, Mehmed had his 19 brothers executed, the oldest of whom was 13. It was a sad, dark day. Ahmed and his siblings did not witness the removal of the 19 corpses from the palace into the narrow streets of Istanbul. All Istanbulites, young and old, mourned, walking behind the funeral procession of the deceased sons of Sultan Murad III. 5-year-old Ahmed and his brothers learned later what it meant. Handan Sultan, as the wife of Mehmed, sadly and angrily watched the tragedy. She thought of many what-ifs. There was no guaranty for anybody.

Mehmed III had a different agenda in his mind, or it was the agenda of Mehmed’s mother, Safiye Valide Sultan, though nobody will ever know for sure. The agenda was revealed in the first days of the throne. It was an attempt to secure his sultanic position by applying the law of sultanic fratricide (x), which means clearing all the obstacles and alternatives in his ruling. Thereby, Mehmed had his 19 brothers executed, the oldest of whom was 13. It was a sad, dark day. Ahmed and his siblings did not witness the removal of the 19 corpses from the palace into the narrow streets of Istanbul. All Istanbulites, young and old, mourned, walking behind the funeral procession of the deceased sons of Sultan Murad III. 5-year-old Ahmed and his brothers learned later what it meant. Handan Sultan, as the wife of Mehmed, sadly and angrily watched the tragedy. She thought of many what-ifs. There was no guaranty for anybody.

One’s loss becomes the other’s gain. Their family, thankfully, was on the winning side. Mahmud, Ahmed’s older brother, naturally became the crown prince, the first choice for the throne. For everybody, it was a new position as well as new happiness and fear. Kids were educated well and being prepared for the throne. Mahmud, as a crown prince, was privileged and more confident than the others were. Ahmed and Mustafa were seriously concerned by the law of fratricide, as they became older. Ahmed believed in “destiny”, taking comfort in that belief.

As per the palace tradition of Ottomans, the Sultan’s mother receives the title of Valide Sultan (Mother Sultan) and ranks the highest in the Harem. During the reign of Mehmed III, the honor was carried by his mother, Safiye Valide Sultan. Being stunningly beautiful, well-educated and smart, Safiye also had a strong personality and had a strong influence over her son. Therefore, Mehmed never increased his wife’s status in the harem. Ahmed knew his grandmother very well. So did Handan,who therefore accepted her authority in the Harem.

The more Mahmud became independent as an oldest son, the more Mehmed III felt concerned about his own throne. The anxiety drove Mehmed so crazy that he finally ended up with a senseless sultanic decision; to execute Mahmud in 1603. He saved his chair, but he also created another dark chapter in the life of Ahmed and Mustafa, then 13 and 12 respectively. Mehmed was relaxed after the event, the childrens' fear factor reached an all time high.

After Mahmud’s disappearance, it now became Ahmed’s turn to be the new crown prince, or the new victim. Sometimes, life does not go as planned. The internal organs of Mehmed’s body, led by his heart, revolted against his nonsensical suspicions. He suddenly died from a heart attack within a year, in 1603 at the age of 37.

Enthronement of Ahmed

While the Ottomans experienced a tragedy in Istanbul, on the other side of Europe, English writer Shakespeare was writing another European tragic story, which was about the Kingdom of Denmark. The year, 1603, became important for both Shakespeare and Ahmed: in 1603, the Tragedy of Hamlet was first published in England, and Ahmed was brought to the throne in Istnbul.

Ahmed’s enthronement was held on 22 December 1603. At the age of 13, just becoming a teenager, Ahmed became the 14th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire. He became the second youngest sultan after Mehmed II, the Conqueror, who was then 12. After Mehmed’s "house cleaning", there was no alternative other than bringing a teenager to the throne.

Among the happiest people were his grandmother Safiye Sultan and his mother, Handan Sultan. Having a teenager in the throne was also good for Safiye Sultan to keep her highest position in the Harem; at least, it was what she thought. Young Mustafa fearfully started to wait for destiny’s final knock at his door.

As the Empire needed, Ahmed sat on the throne right away, but missed the early leadership training opportunity of being a princely governor in another province. This made Ahmed the first sultan coming to the throne directly from the palace. Naturally, extraordinary times create their own rules. His early enthronement actually taught him more, as he learned life first hand and at a young age. His big advantage was to have been physically developed from a very early age, and maybe his heightened survival instinct helped as well.

Ahmed was not circumcised when he came to the throne. This never happened in the royal family before. Therefore, he was immediately circumcised within a month. A private ceremony was held for him, though his father’s circumcision ceremony in 1582, which lasted for 52 days, was the most expensive and extraordinary circumcision party ever.

Because of his age and the condition, he was guided by his mother and other state officers. Ahmed was so wise. He was deeply involved in state matters, and well understood the issues. He learned fast, and keenly equipped himself with the crucial knowledge of management.

Replacing the Law of the Sultanic Fratricide with Cage

Ahmed personally witnessed all of the recent family tragedies caused by the law of the sultanic fratricide, legalized by Mehmed II, the Conqueror (1451-1481). The first thing he did as sultan was to abolish the law. From then on, executions were no longer legally accepted as an excuse for the throne. Instead, Ahmed introduced a new sultanate law, which stated that the eldest living male has the right to inherit the sultanate. According to the new rule, the upcoming princes were confined in the Harem of the palace until their adulthood, after then they were removed to the special section of the palace, called the Kafes (Cage), where they waited for either coronation or death. They were comforted in the meantime by infertile concubines and they were only allowed to have limited occupations. None of the princes were permitted to go to other provinces as a princely governor for their leadership and administrative training. Unfortunately, this new rule did not became a panacea either, as it did not prevent Osman, Ahmed’s oldest son, from being killed in 1622 by the janissaries in the Yedikule Fortress.

Ahmed’s decision about his younger brother, Mustafa, was clear. He would not be killed, but be kept in the Kafes section of the harem in the Topkapı Palace until further notice. That moment became the beginning of his 14-yeasr of confinement in the Kafes. Staying in a small studio apartment for 14 years made Mustafa cognitively challenged.

Sultanate of Women and Safiye Sultan

In the very early period of Ahmed’s reign, Safiye Sultan could not help meddling in the politics in the palace. Being the third generation of the “Sultanate of Women” period of the empire (after Hürrem Sultan and Afife Nur Banu Sultan) Safiye Sultan was still the most powerful and influential woman in the palace. Her confidence came from a wide network of her strong connections. This left Ahmed and Handan in a secondary position in their own Harem and palace. Ahmed made up his mind easily. Eventually, Safiye Sultan was removed to the Old Palace. She had no choice, but left the Topkapı Palace. At the outside of the gate, when she looked back at the palace the last time, only she knew what she angrily thought. She spent the rest of her life in confinement.

The removal of Safiye Sultan positioned Handan Sultan to be the new most powerful Valide Sultan in the Palace. Handan Sultan decreased her own stipend to a third of what Safiye Sultan received from the state. This public relations gesture was necessary to be seen by the people as a fair mother of an underage sultan.

Sultan Ahmed was young, but he had his own harem in the palace. The young sultan’s virility made him the youngest father in the empire. On 3 Nov 1604, almost a year after Ahmed’s enthronement, Mahfiruz Haseki Sultan received the honor of being the first concubine to give Ahmed his first son. Ahmed named him Osman, which was the name of the founder of the Ottoman Empire. Osman became the first Ottoman prince born in the imperial capital of Istanbul. By then, princes, including Ahmed, were born in other provinces where their fathers were governors. Osman, with the nickname of Young Osman, later became the 16th sultan between 1618 and 1622. Thankfully, Ahmed did not see the sad ending of Osman’s life.

The first couple of years of her son’s reign, Handan helped him in the background. This period was quite educational for Ahmed, as Ahmed was still growing up. The Harem was shaken by the news in November 1605; it was the death of Safiye Sultan at the age of 55. A couple of weeks later the shocking news turned the Harem upside down. This time, it was about Handan Sultan who died at the very young age of 29. It is rumored that she was poisoned. Helping her son during the first couple of years of his reign was probably the most valuable gift she gave her son, Ahmed.

During the reign of her husband, Safiye Sultan wanted to build an imperial mosque. She struggled with the difficulties caused by the landowners, nevertheless managed to purchase the land in Eminönü. The construction of the mosque started in 1597, but the project was interrupted by the financial difficulties and the past owners of the land. After Safiye Sultan died in 1605, Ahmed dismissed the Architect Dalgıç Ahmed and terminated the construction when it reached barely above ground level. The project was left to its fate.

In 1663, 66 year later, Safiye’s half-finished mosque was completed by Valide Turhan Sultan, the mother of Mehmed IV (1648-1687). Today, it is the New Mosque (Yeni Camii) in Eminönü, also known as the Valide Sultan Camii, one of the best imperial mosques in Istanbul. Here is the question; why did Ahmed not then complete the half-finished mosque, but preferred starting a brand new mosque from scratch, a much more expensive venture? This probably shows his strained relations with his grandmother, Safiye Sultan. One thing was certain, that building both of them would have been financially impossible.

New person in his life, Kösem Mahpeyker Sultan

From 1605 on, the 15-year-old Ahmed continued his journey with the help of his confidants, or tried. That was the year when Cervantes published his masterwork “Don Quixote de la Mancha”. The Spanish novelist wrote about the journey with its imaginary characters, but Ahmed’s journey was tangible and full of hurdles and his destiny was real. Losing his mother was quite painful; therefore, he needed to pause for a while. As he wanted to forget everything, he followed his desires and spent his time with his women, which caused a disastrous scandal. Grand Vizier Dervish Mehmed Paşa paid for Ahmed's indiscretions with his head in 1606. This brought Ahmet back to reality.

From 1605 on, the 15-year-old Ahmed continued his journey with the help of his confidants, or tried. That was the year when Cervantes published his masterwork “Don Quixote de la Mancha”. The Spanish novelist wrote about the journey with its imaginary characters, but Ahmed’s journey was tangible and full of hurdles and his destiny was real. Losing his mother was quite painful; therefore, he needed to pause for a while. As he wanted to forget everything, he followed his desires and spent his time with his women, which caused a disastrous scandal. Grand Vizier Dervish Mehmed Paşa paid for Ahmed's indiscretions with his head in 1606. This brought Ahmet back to reality.

Ahmed, meanwhile, completed in 1608 the construction of the new and large masoleums for the people who already passed away, his parents, Mehmed III and Handan Sultan. Built in the garden of Saint Sophia by the architect Dalgıç Ahmed Ağa, the octagonal mausoleum would host his children in the coming years. Unfortunately, it turned out that Ahmed needed such a large mausoleum for his family.

Another girl's journey brought her to this palace at this time, Kösem Mahpeyker Sultan, first arriving at the palace as a young concubine, who caught everyone's attention in the harem by her charm, beauty and wisdom. She used her skills and finally managed to impress Sultan Ahmed. Both were almost the same age. Kösem Mahpeyker, born in Bosnia, merged her destiny with Ahmed’s in 1612 by giving him a son, Murad. Ahmed’s first son, Osman, was 8 years old at that time. This birth promoted Kösem to a higher level in the Harem as a mother of the Sultan’s son. Her position was cemented in 1615 after the birth of her second son, İbrahim. Kösem Mahpeyker Sultan, in later years, would become a significant player in the history of Ottomans by controlling the empire as a mother and a grandmother of three sultans (two adults and a child) for longer than a decade. It did not happen during the reign of Ahmed, but after him. Due to Kösem the “Sultanate of Women” period of the empire was resumed. (x1)

Ahmed I’s Proof of Piety

Ahmed was the sultan of the biggest empire of his time and there was no single human being in a higher position than he had. On the other hand, he had nobody around him to trust, or to ask for protection.

He found his strength in Sufism. Later, Kösem also joined him. Together, they attended the dergâh (lodge) of Aziz Mahmud Hüdâyi in Üsküdar, Istanbul. Both never surrendered to the heavy burden of life, instead, they steered their destiny by their strong will and wisdom. Over all, Ahmed became a successful sultan with his experience and decisions. He owed this to his belief in Sufism. Until his last day, he stayed a pious person. Ahmed wrote poems under the nickname of Bahti (meaning “destiny”). His poems were mostly religious.

Administering State Matters

When he came to power, Sultan Ahmed found many unsolved issues at hand. One of them was the 15-year-old war with the Habsburgs. After the death of his experienced Grand Vizier, Sokolluzade Lala Mehmed Paşa, Ahmed, with the help of his confidants, made up his mind. Realizing that it would not be possible to advance in Europe, he decided to finalize the conflict by signing an agreement on 11 November 1606 with Austria. After the negotiations, the treaty was signed at Zsitvatorok, at the mouth of the Zsitva River, which flows into the Danube (today, in Slovakia). Neither side was happy afterwards. This means that the Peace of Zsitvatorok was an effective agreement. Ahmed moved his resources to other places in the empire.

Celâli (or Jelâli) Revolts, which were rebellions in Anatolia against the Empire, became a major problem for the Palace. They took their name after Şeyh Celâl, who first organized the reactions against the government in Yozgat a century earlier in 1519. The revolts were caused by social and economic problems, such as a depreciation of the currency, and heavy taxation. The rebellions were also caused by sectarian events in Anatolia. The rebellions were not intended to overthrow the Ottoman government, but they aimed to demonstrate their frustrations against the palace.

During the reign of Sultan Ahmed, the latest wave of revolt lasted 15 years and it rose to intolerable levels. Therefore, the sultan felt they had to be put to a stop in some way. After three years of fighting against the rebels, Kuyucu Murad Paşa, the grand Vizier of Sultan Ahmed, ended the conflict in 1610. Thousands of people were killed during the fighting. The grand vizier took his nickname of Kuyucu (meaning a hole-digger) after killing so many people during the skirmishes. The issue, being a major problem in the beginning, turned to be a major victory for Sultan Ahmed in the end. This case lifted his credibility throughout the empire.

Presented to Europe after the discovery of America in 1492, tobacco was brought to Istanbul almost a century later by British and Spanish ships. Tobacco, imported into the Ottoman Empire as a regular commercial product around the time of Ahmed’s accession to the throne, was introduced to the people of the Ottoman Empire as a medicine for every disease. This attractive introduction did not convince the religious scholars and the empire. Therefore, tobacco was banned in 1609 by Ahmed, who also banned alcoholic drinks in 1613.

Building Monuments

The Italian scientist Galileo (1564-1642), the father of modern observational astronomy, improved the aperture of the telescope to see the farthest distances in the sky, and eventually achieved his dream of seeing the moons of Jupiter in 1610. Ahmed wanted something similar; to put the trajectory of the empire on the right path, by clearing the obstacles, so that he too could see further.

He, actually, saw the future very clearly, and built a religious monument which millions visit each year. As a pious person, this project was very important for Ahmed. He spent long hours at the construction site. Probably, he became the happiest person when the construction of the Sultanahmet Mosque (also known as the Blue Mosque) was completed on 9 June 1617.

Sultan Ahmed accomplished many land developments in Istanbul. He built a “pleasure” pavilion in 1608 in the Topkapi Palace, now called the Privy Room of Ahmed I (Kasr-ı Ahmed), located in front of the Privy Chamber of Murat III. Designed by the architect Sedefkâr Mehmet Agha, the walls of the pavilion are decorated in stunning green colored Iznik tiles. It is believed that the small wooden writing desks decorated with mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell were designed by Sedefkâr Mehmet Agha.

Sultan Ahmed also constructed a new imperial garden (Hadaik-i Hassa) on the Bosphorus, now called Dolmabahçe. The word ‘Dolmabahçe’ means ‘filled-in garden’ in Turkish, as the outer garden, established on land, was reclaimed from the sea on the shore of the Bosphorus. Ahmed built a short-lived palace, called the Beşiktaş Palace. Two centuries later, Sultan Abdülmecid (1839-1861) built the Dolmabahçe Palace Complex in 1856 on that field.

Sultan Ahmed also expanded the royal land in Istanbul by including Kazancıoğlu Gardens, which was the large area between Beşiktaş, Ortaköy in the north and Balmumcu in the west. Then uninhabited woodland is now occupied by two great palace complexes, the Çırağan Palace and the Yıldız Palace. Ahmed also undertook a comprehensive repair of Hagia Sophia (Ayasofya).

Turkey and Holland celebrated in 2012 the 400th anniversary of their trade relationship. Both countries owe their commercial ties to Sultan Ahmed. In 1612, Sultan Ahmed granted the same commercial privileges to Dutch merchants as the French, Italian and English had. During the reign of Sultan Ahmed, many European engravings (mostly Dutch) and books came to the Topkapi Palace. Illustrated albums with figures wearing European costumes were produced in Istanbul.

One of Ahmed’s contemporaries was the Scottish mathematician, John Napier who discovered logarithms in 1614 to simplify calculations.

Final Years

With the exception of the early period of his enthronement, when he was very young and needed experienced grand viziers, Ahmed was personally involved in state matters. During his reign, Ahmed worked with seven grand viziers (an equivalent position of a prime minister), two of whom were executed.

Being the 14th Sultan of the Empire, Sultan Ahmed could not stay in the throne longer than 14 years. He was only 27, when he passed away from typhus in Istanbul on 22 November 1617, the same year his well-known Blue Mosque was completed. He was unable to attend his mosque to pray for long at all, but his masterpiece became his permanent resting place.

The mausoleum of Sultan Ahmed also houses his wife, Mahpeyker Kösem Valide Sultan, and two of his sons, Sultan Osman II (1618-1622) and Sultan Murad IV (1623-1640).

In later decades, two more sultans carried the name of Ahmed in order to honor his reputation. The neighborhood, where this complex is, carries his name, the Sultanahmet Square. In today’s language, “Sultan Ahmed” is used as one word, “Sultanahmet”.

Upon the death of Sultan Ahmed, his brother, Mustafa (1617-1618), was brought to the throne as the 15th sultan, instead of Ahmed’s 13-year-old first son, Osman, who was from his first wife, Mahfiruz Sultan. Mustafa’s enthronement was unprecedented, as it became the first time in the empire that the throne passed to a brother, instead of a son. It was actually Kösem Mahpeyker Sultan’s plan in order to bring her own son to the power. She knew that Mustafa’s presence in the throne would be temporary, as his mental health, because of his confinement, was not strong enough for the throne. Kösem needed time for her children to come of age. Everything happened as she planned. However, this plan did not prevent her from being sent away from the palace.

(x1) Kösem Mahpeyker Sultan gave birth to two sultans in the Ottoman Empire. The dynasty continued from her bloodline. One of her sons was Murad IV (1623-1640), born in 1612, and became the 17th sultan. The other son was İbrahim I (1640-1648), born in 1615. She could not curb her ambition and had İbrahim killed, and then brought her 6-years-old son, Mehmed IV (1648-1687) to the throne.

Baki Tezcan, (2010), “The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World”, Cambridge University Press, USA, p.115

Britannica.com

Caroline Finkel, (2007), “Osman's Dream: The History of the Ottoman Empire”, Basic Books, USA. p. 184-195.

Fehmi Yılmaz, “Bağımlılığın Tarihi: Osmanlı'da Tütün”, Istanbul Medeniyet Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi

Gábor Ágoston and Bruce Masters, (2009), “Encyclopedia of the OTTOMAN Empire”. Facts of File, An Imprint of Infobase Publishing, p. 22

Gunsel Renda, (2006), “The Ottoma Empire and Europe: Cultural Encounters”, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation (FSTC). United Kingdom, p.11

Gülsüm.Ezgi Korkmaz, (2004), “Sûrnâmelerde 1582 Şenliği” Bilkent Üniversitesi, Ankara

İlber Ortaylı, (2010), “Kösem Sultan'ı yargılamak zor”, Milliyet Newspaper.

Kenneth Meyer Setton, (1991), “Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century”, The American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, Volume 192, p.22-27

Leslie P.Peirce, (1993), “The Imperial Harem: Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire”, Oxford University Press, p. 98-225.

Mesut Uyar, Edward J. Erickson, (2009), “A Military History of the Ottomans: From Osman to Atatürk”, Greenwood Publishing Group, USA, p.96-98

Michael Keating, (2007), “Feminine Roles in the Ottoman Empire: The Significance of Women during the Sultanate of Women Period.

Selim Aydin, (2002), “Bahti (I.Ahmed)”, Sizinti Dergisi, Kasim 2002, Yil 24, Sayi 286.

Tulay Artan (2006), “The Cambridge History of Turkey, 19-Arts and architecture” p. 454

Ahmet Ihsan Toksü